The untold history of EGM

When you’re talking about EGM (Electronic Gaming Monthly), the same stories tend to get told and retold.

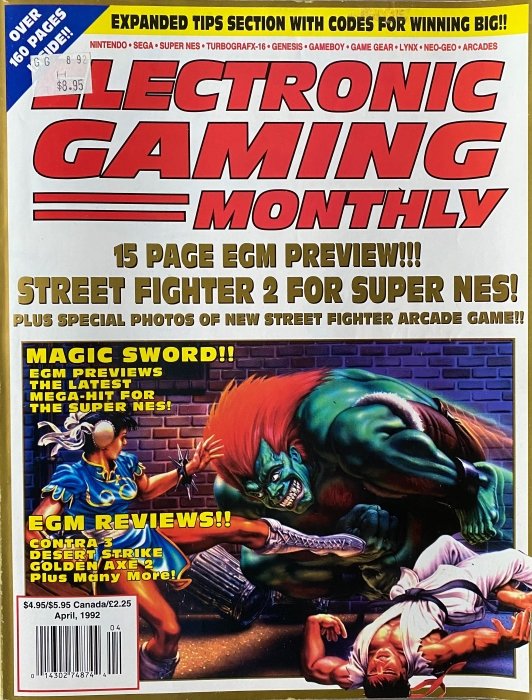

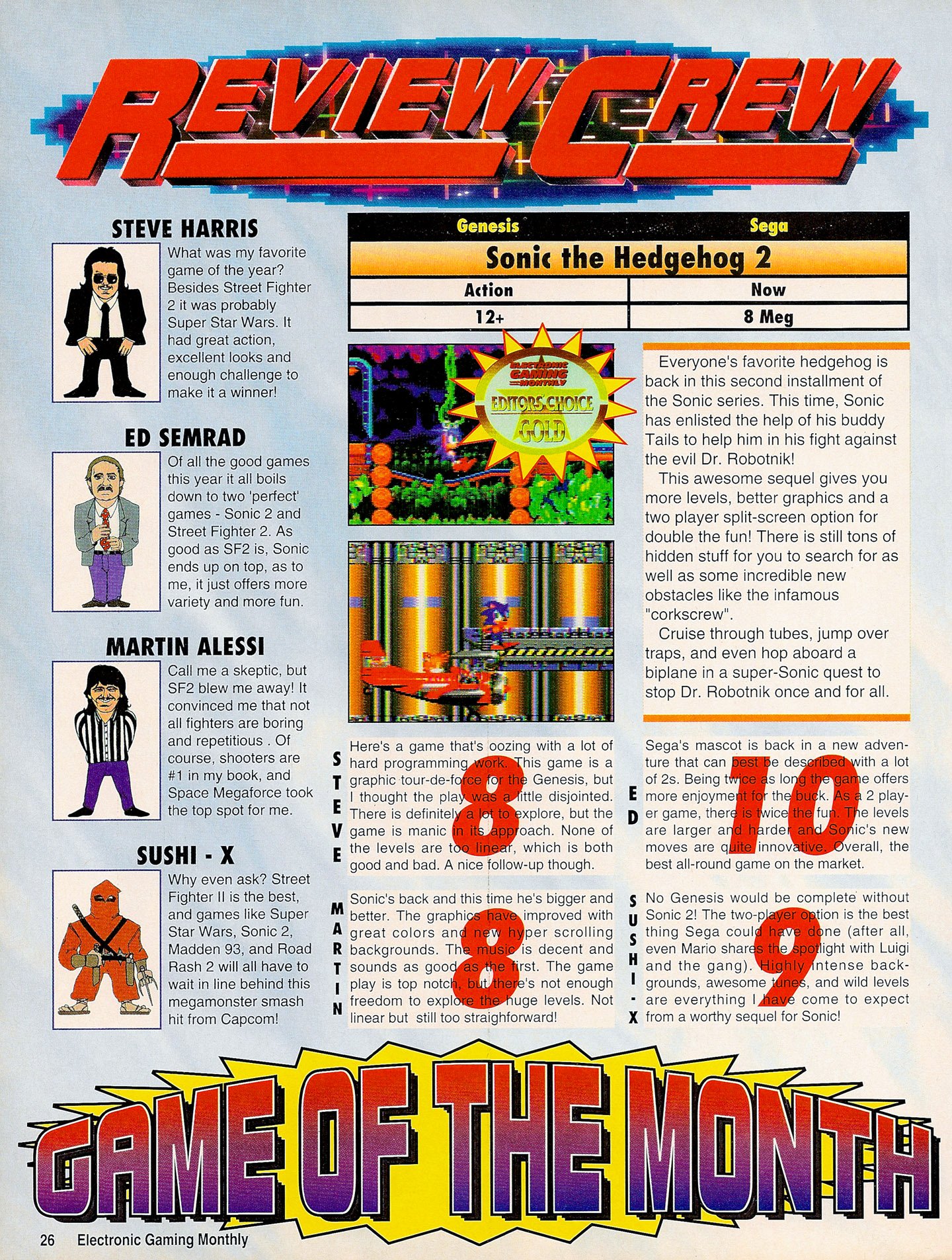

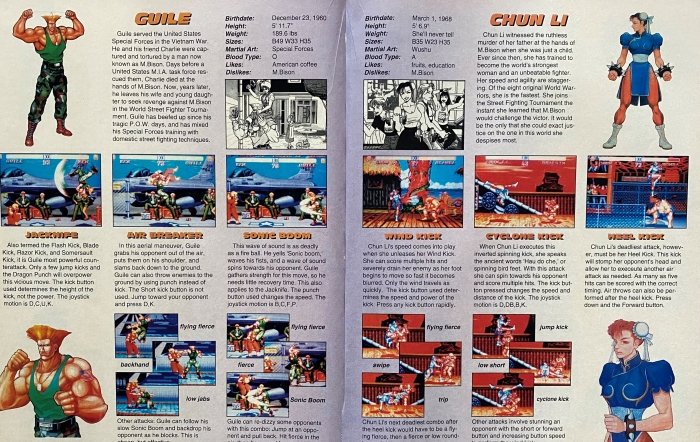

Chances are, if you’re reading this, you’ll know all about EGMs 4-person review panel that was cribbed from Japan’s Famitsu magazine. You’ll be familiar with Sushi-X and his hatred of anything Gameboy, and you’re well aware of the infamous Sheng Long April Fools joke.

Great stories, sure, but we’ve all heard them before.

What no one talks about is the impact EGM had on the broader, international video game market. How it provided a counterpoint to the U.K. gaming media, offered a dedicated resource for Japanese imports, and shaped the gaming tastes of an entire generation of kids.

Same-same but different

The video game industry is almost entirely homogenised these days. Same-same all around the world. But it wasn’t always like that.

Case in point - the video game crash of 1983. In the U.S. this is a defining point in the evolution of the video game industry. But for those of us in Europe and other PAL territories it’s little more than a footnote. Everyone was too busy with their Spectrums, Commodore 64s and other micro-computers to worry about the fate of Atari and unsold ET game cartridges.

The evolution of video game magazines is another example of the disconnect between the U.S. and the rest of the world. By the late 80s PAL gaming was awash with British magazines and their irreverent, fan-focused take on the industry. This template was established with publications like Crash and Zzap!64, which in turn provided a blueprint for what was to follow with CVG, Mean Machines and various others.

U.S. video game magazines went down a different evolutionary road in the 80s. Julian ‘Jaz’ Rignall covers this extensively in his article for US Gamer, but the short version is that U.S. magazines were more reliant on ad sales than their U.K. counterparts, which impacted the language used and what they could get away with.

As Jaz notes, “In the U.S. there was far more nervousness about upsetting publishers, because pulled ads put a magazine's bottom line in jeopardy. This resulted in a tempering of language – or simply not covering a game if its coverage would be controversial.”

This was reinforced by the family friendly, officially licensed Nintendo Power magazine, which was practically required reading for a generation of kids with an NES under their TV in the late 80s.

EGM changed all that. Founded by high school drop-out Steve Harris with the proceeds from video game tournaments, it adopted a more honest, teen friendly approach. In the process it plugged a hole in the market, and helped drag U.S. gaming media into the new decade.

As Steve explained in a 2009 interview with Engadget, “The early issues of EGM were all about being first with the information and being honest in our assessment of the games and products we reviewed. My philosophy, born from earlier experiences writing for coin-op trade magazines, was that we had to know who we were writing the magazine for and focus on delivering to that audience regardless of the fallout. As long as we wrote the magazine for the readers I knew we would be fine.”

PAL vs NTSC

EGM didn’t just shake up the U.S. publishing landscape, it provided an alternative to the U.K. gaming media we knew in PAL territories. It’s reference points, attitude, design and console coverage was a complete break from what CVG and Mean Machines readers knew.

So when import copies of EGM first began to appear in PAL markets in the early 90s it was like a glimpse into an alternative reality. At once familiar, but also totally different to what we had known.

In this world the NES still reigned supreme and the associated ads ran thick. The Turbografx-16 was slugging it out with the Sega Genesis, the Super Nintendo was strangely deformed with purple highlights, and no one had ever heard of the AMIGA 500 or cared about weird little Spectrum games.

Introducing Dan ‘Shoe’ Hsu

Dan ‘Shoe’ Hsu has a better understanding of the dichotomy between U.K. and U.S. publishing than most. He was editor of EGM between 2001-2008 and a staff writer since 1996. But before any of that, he was just another kid who loved video games and was looking for a way into the industry.

Speaking on a recent ZOOM call, Dan explained that his childhood reading material was pretty typical of any other North American kid who loved gaming in the early 90s. In other words, there was no CVG, no Mean Machines or Super Play.

“EGM was my favourite, followed by Next Gen. I read them both regularly before I got into the industry. Then Nintendo Power further after that, and occasionally other magazines like Gamepro or Game Informer, Game Fan.”

When he graduated from University with a degree in statistics, he decided to put numbers to one side, and see if years of dedicated reading might provide a more interesting career path.

As he explains, “I was just kind of aimless [after college], didn’t really know what I wanted to do in life. I was a big video gamer, and an EGM reader, and my girlfriend at the time suggested I apply at companies that I would like to work for, rather than where I could apply my college education to. So I sent my resume and cover letter to maybe 20 game companies and outlets such as EGM.”

“Nothing happened for months, so I thought that was just a bust, but then I got a call from editorial director at EGM, Joe Funk. He really liked my cover letter, said they were looking for writers, and asked me to turn in some more writing samples. I thought it was a joke at first, like maybe one of my friends was pranking me. So anyway, I sent through some samples, he liked them and asked me to come down for an interview, and I got the job.”

EGM goes big

When Dan joined EGM in 1996 it was already well established in gaming circles and had the reputation and resources to churn out mammoth 400-page issues leading into the holiday season.

But if you ask Dan what set EGM aside, and why it’s still so fondly remembered after all these years, he’s quick to mention the staff and their respective personalities.

“EGM was very much about letting the personalities of the writers shine. So whether that was the rumours section with Quarterman, or Trickman Terry, or the reviewers, you kinda got to know them by name. When I went and interviewed at EGM, I was like, ‘Oh, you’re [insert name], I’ve been reading your stuff, I know who you are’.”

“I know the review crew was [also] really popular. Famitsu [magazine from Japan] had a similar format. EGM stole that format, and each game would get a little write-up. It’s kinda counter-intuitive, you get very little information, but you see 3 or 4 scores right away, so you get a good feel for what the magazine or staff think of that game.”

Just as importantly, EGM became the go-to-source for international gaming news and the burgeoning import scene.

“I know for me as a reader, even before I worked there, one of the reasons I read it was they always seemed on top of everything new that was coming out, and they had sections about what’s coming from Japan. This is the 90s, so this is pre-internet, and this is where you’re getting all the information from. So EGM was very aggressive about global coverage vs. just a domestic market.”

Running up that hill

None of this was occurring in a bubble, and the UK gaming media was also covering imports from both the U.S. and Japan, but as far as resourcing and accessibility goes, they were fighting an uphill battle.

As Dan explains, “The advantage we had as American magazines is a much larger market. The impression I had was that our [international] distribution was also a little bit more advanced, so we were able to get some magazines overseas, and that had a snowball effect. [It meant] we had a larger audience, so we were able to secure more exclusives.”

“Having that access, the success kind of built upon itself. It means companies come to you and say, ‘We want to debut or announce a game through EGM because it’s the biggest magazine out there or one of the best selling ones’.”

“You had magazines like Next Gen or Edge that were viewed as more prestigious, so it was a PR win for a publisher to get coverage in them. But EGM was a little more mainstream, and so they had a wider reach, and once you start getting those exclusives your readership expands, and the success builds upon itself.”

Meanwhile, back in the UK

If EGM had global ambitions, it only had a cursory interest in its international rivals. “There were a lot of influential magazines abroad, like Edge, or Famitsu, that we knew by reputation, but we never got the sense that they had huge distribution [in the U.S.].”

Regardless, the different publications rarely had a chance to meet face to face. With localised release schedules and PR teams, Dan says it was rare to encounter foreign publications and their writers. “Even if we were at the same international events, demos and PR would be scheduled according to regions, so there was little chance to meet.”

The U.K. gaming media took a similar view. As Dean Mortlock, former editor of Sega Power and main guy behind the newly launched Sega Powered confirmed in a recent interview, “We got all the [U.S. magazines] in the office, but we never really considered them competition.”

The internationalist

To look back at EGM and the U.K. gaming media in the 90s is to view two sides of the same coin. The Sega Genesis to someone else's Mega Drive.

Having access to both didn’t just expand your Christmas wish list or desire for obscure Japanese imports, it expanded your worldview. EGM offered an alternative take on the gaming industry to the one I knew from the U.K. magazines.

Reading both provided a global overview and a crash course in licensing, logistics, freight and geopolitics. All of it cloaked in 90s video game mascots and magazine covers with too many exclamation points(!!!).

Or maybe I’m reading too much into all this, and picking up EGM alongside Mean Machines was just a way to pass the time and spend some pocket money.

But whenever an air-freight copy of the magazine surfaced at school it was poured over with the same intensity as a Playboy issue featuring Pamela Anderson. Which is high praise if you’re talking about a bunch of teenage kids in the 90s.

….